Adapted from an article by Dr Jason Paul Mika – Ngāi Tūhoe

Māori entrepreneurs with a strong sense of cultural identity and guardianship over the land and the sea are driving a boom in Māori business.

Māori businesses now account for an economic asset base of more than NZ$42.6 billion, according to the latest estimates. Small and medium-sized enterprises make up the largest part of the Māori economy.

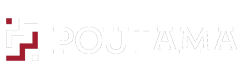

These entrepreneurs are building on a business approach with ancient roots – a Māori way of thinking and doing business and its ability to reconnect with our common heritage as descendants of Papatūānuku, mother earth.

Drivers of Māori entrepreneurship

A number of developments are likely to be driving this. Chief among them are Māori frustration and anger over the negative effects of loss of land, language, culture and tribal autonomy over successive generations. The response has been a cultural renaissance. It started in the early 1970s and set out to reaffirm Māori as tangata whenua (people of the land) with enduring rights as the indigenous people of Aotearoa.

Out of this period of tumult came the Crown’s attempt at peace and reconciliation with Māori through the Waitangi Tribunal. Settlements under the Treaty of Waitangi, which was signed by Māori chiefs and representatives of the British Crown in 1840, are probably the single-most important factor in changing perceptions of the Māori economy.

However, settlements made up only about 1% of the NZ$36.9 billion Māori economic asset base in 2010. It is the 15,600 or so Māori small and medium-sized enterprises, managing NZ$26 billion in assets, that make up the largest part of the Māori economy. Bankers, investors and suppliers are drawn to Māori enterprises as potential partners, eager to understand how to modify their offerings and methods with this market in mind.

Kawerau Dairy offers an example of this through partnering with Cedenco Dairy Ltd’s Japanese parent, Imanaka. The Japanese understand the cultural connect and are at ease with whānau and intergenerational business. Air New Zealand’s increasing use of te reo also springs to mind. While casually introduced, it belies a much sterner “behind the scenes” challenge to normalise Māori language and culture within our national carrier.

Māori ingenuity in business

The power of enterprise to transform Māori lives was embraced when a decade of Māori development was set in motion following the Māori Economic Summit (Hui Taumata) in 1984. Within its remit, enterprise development was identified as an important means of realising Māori aspirations for self-determination.

Somewhat against the tide of the then government’s withdrawal of direct support for industry, a number of initiatives to assist Māori enterprises were established following Hui Taumata. Some of them still exist today, including Poutama and Māori Women’s Development Incorporated.

An ideal model for enterprise assistance

History shows that public funding of enterprise assistance for Māori ebbs and flows with changing political ideologies. Dr Mika’s doctoral research shows that Māori businesses operate on an uneven playing field where Māori providers face a different level of scrutiny as to their value for money. Māori enterprises need both Māori-specific and mainstream support, but the knowledge of what works for Māori has so far been limited to policy evaluations rather than empirical research.

Mika’s research found that Māori entrepreneurs identified seven main features of the ideal model of enterprise assistance:

- Operates within an entity substantially owned and controlled by Māori;

- Partially government funded;

- Delivery by Māori in partnership with mainstream providers;

- Multiplicity of assistance (e.g. information, advice, facilitation, training, grants, and finance);

- Cultural authenticity and flexibility;

- Long-term relationships with Māori enterprises;

- Varying assistance over the business life cycle.

Research identifies three key competencies that consistently matter to Māori entrepreneurs: cultural competency (knowledge of the Māori language, culture and history and the ability to use it), relational competency (time invested in forming relationships with Māori entrepreneurs) and technical competency (delivering on promises).

It also identifies principles that providers (Māori and mainstream) can use to evaluate their assistance against Māori entrepreneurs’ needs and preferences. With such change in enterprise assistance, all of Aotearoa is set to benefit from the “new normal” – Māori entrepreneurial success.